It is said that we can survive 3 hours without shelter, 3 days without water, 3 weeks without food but little more than 3 minutes without breathing. Normally, the function of breathing takes place without any direct help from us – it is continuous and we do not think about it, assuming there is no underlying, pathological problem. Most people, when they take part in sports, exercise or even a brisk walk, become aware that they are not breathing well and that they are in oxygen deficit. Sometimes, to correct this problem, they may try breathing exercises. These exercises usually involve ‘pushing out’ either the chest or the abdomen – requiring a lot of effort for very little air.

Generally, the reason why we are unable to take a full breath is that our muscles are holding the ribs stiffly instead of allowing them to move. Breathing exercises do not seem to address the problem of why the ribs are so fixed and held. Because our poor postural habits have interfered with the reflexes that support us, abdominal and chest muscles contract to assist the stability of the trunk. Breathing is then restricted and becomes shallower and more rapid.

What is Breathing?

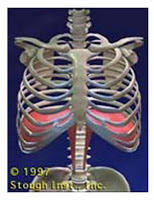

We breathe in to gain oxygen (which we use to make energy) we breathe out to lose the waste products of energy production (carbon dioxide). Poor breathing can lead to feeling tired and lacking energy because the cells of your body may not be getting enough oxygen and there is insufficient elimination of carbon dioxide. Due to its intrinsic elasticity, the rib cage, if it is not held down by muscular tension, tends to lift and widen itself. To breathe in all we need do is allow the rib cage to expand which, in turn, increases the volume of the lungs. A system of breathing reflexes uses, as much as possible, the intrinsic elasticity of the rib cage. These reflexes use appropriate muscles to expand the space of the rib cage even further to make room for the volume of air your lungs are demanding. The Air pushes into the lungs by air pressure. Air pressure is approximately 15lbs per square inch or 1kg per square centimeter, therefore, we do not have to ‘pull’ air in. All we need to take care of is that we are not holding the ribs down or blocking the airways.

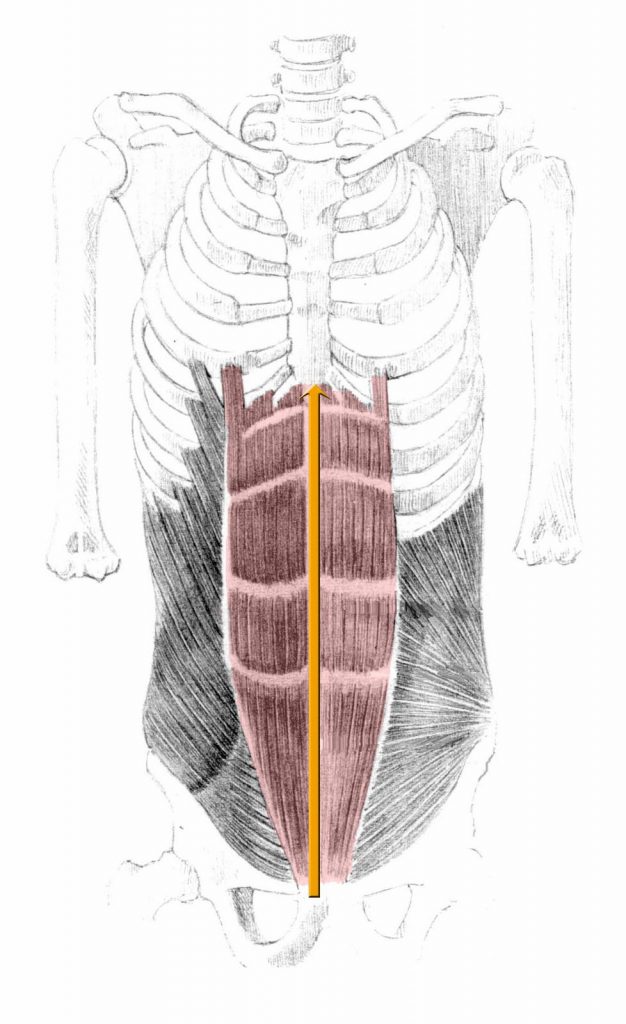

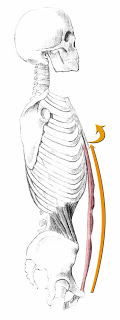

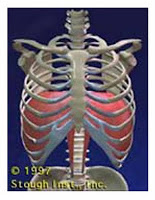

Rectus Abdominis

This connects the pubic bone to the ribs at the level of the heart. When it contracts, it pulls the ribs down. Allowing rectus abdominis to release from pubic to the ribs releases the abdomen, ribs float and become less fixed so that there is greater freedom of breath. This is why sit-ups are harmful. The function of rectus abdominis is to allow the intrinsic upward release of the rib cage. They should not be trained to hold the ribs down.

Allowing rectus abdominis to release from the pubis to the ribs releases the abdomen, ribs float and become less fixed so that there is greater freedom of breath.

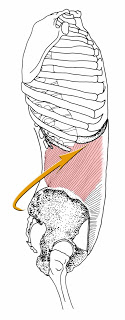

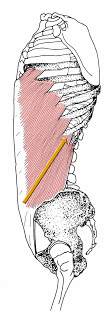

The Oblique Muscles

Internal and external oblique muscles produce the curve of the waist. They play a role in the spiral/twisting movements of the body such as swimming, walking and running. They affect breathing by pulling down on the ribs when they contract. Combined with the interferences of rectus abdominis, etc. they tend to hold the ribs in a depressed position, like a corset, making breathing more effortful. We tend to compensate subconsciously by trying to breathe harder or use ‘abdominal breathing’ i.e. instead of the ribs moving, the abdomen pushes out. Your lungs are not in your abdomen.

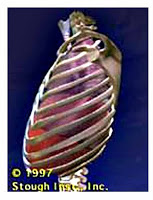

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a large sheet of domed muscle with a stalk that attaches to the spine so that it looks like a lop-sided mushroom. It attaches to the lower end of the breastbone, the spine and the floating ribs. The diaphragm rises to achieve maximum exhale so that air pressure inside the chest cavity decreases. The air pushes into the lungs by the force of the surrounding air pressure at 15lbs per square inch so that internal and external air pressure becomes equalized.

The only part of the breathing cycle over which we constructively exercise any element of control is on the out-breath to talk, sing and play a musical instrument. Provided there is not collapse during the out-breath and the natural lengthening tendency of the spine has been maintained, the in-flow of breath will freely match the expenditure of the out-flow of breath.

Breathing then has very little to do with raising and lowering the shoulders or pushing the abdomen in and out. The torso remains lengthened and there are a smooth in-flow and out-flow of breath.